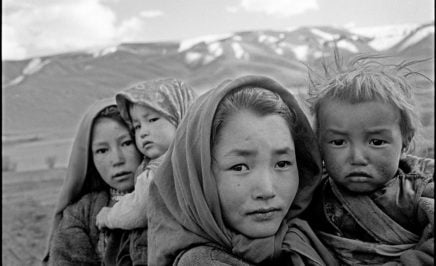

Amnesty International’s Secretary General reflects on our new report on the mounting threat and violence facing those on the front line standing up for women’s rights in Afghanistan.

In Afghanistan’s eastern Laghman province, Shah Bibi is the director of the Department of Women’s Affairs, and continues her work to strengthen women’s rights despite multiple death threats having forced her to move to a different province. “Every day when I leave home I think that I will not return alive and my children are as scared as I am about a possible Taliban attack against me,” she told Amnesty International for a report on women’s human rights defenders in Afghanistan released today.

“Every day when I leave home I think that I will not return alive and my children are as scared as I am about a possible Taliban attack against me.”

Bibi’s two predecessors — Najia Sediqi and Hanifa Safi — were killed within six months of each other in 2012, one by gunmen in broad daylight and another in a car bombing. In a familiar story, relatives told Amnesty International how regular death threats had been met with no response by authorities, despite the women’s repeated pleas for protection. To this day, no one has been held responsible for their killings.

Considerable risk

Bibi’s story is far from unique. We spoke to more than 50 rights defenders and their family members from all walks of life. In Afghanistan, they are not confined to a small group of activists — anyone who uses their public position to advance the rights of women and girls fits this category. Most put themselves at considerable risk for their cause.

There is the police officer whose house was targeted in a grenade attack after highlighting gender discrimination in the police force. There is the teacher who survived a car bombing after she had campaigned for a girls’ school in her province. There is the Pashtun doctor who lives with constant threats, and who has seen her brother killed and her young son badly wounded because of her work. Her ‘offense’? Providing medical services to women and girls who escaped domestic violence, some who had been raped by their male family members.

But defending women’s rights is not restricted to female activists only. Although our report focuses mainly on women, across Afghanistan many men are also championing their cause. We spoke to ‘Mirwais’, for example — a young lawyer who works for a women’s shelter in Kabul, providing refuge to those escaping domestic violence.

No protection

Through our research, a clear pattern emerges of institutionalised indifference on behalf of the Afghan authorities to threats and attacks against these women and men. The government has systematically failed to provide a protected environment for them. Again and again, the same pattern came up in interviews: police, prosecutors, and courts consistently refuse to take threats against women human rights defenders seriously. Few investigations are launched into complaints of attacks, and prosecutions and convictions are even rarer. This impunity, where perpetrators are almost never held to account, only entrenches a culture of violence against women’s rights activists.

Many women also noted how even when they were afforded protection, it was often not as substantive as that given to their male colleagues or counterparts.

Many women also noted how even when they were afforded protection, it was often not as substantive as that given to their male colleagues or counterparts.

What is so dismaying is that Afghanistan has a fairly robust legal framework aimed at protecting women and those defending women’s rights. The problem is that these laws too often exist on paper only. Government bodies and officials charged with protecting women are under-resourced and lack the support to carry out their work.

The Elimination of Violence against Women Law, passed in 2009, criminalised a range of violent acts against women and was a landmark achievement for women’s rights. Years on, it remains sporadically enforced — even when women dare to report domestic violence or other attacks, conviction rates are woefully low.

Bravery

But our report is not just a story of gloom and misery — it is also a celebration of these brave people. From running women’s shelters, championing gender equality in government, to building up a substantial network of civil society groups, Afghan women themselves have fought hard for some significant gains since 2001.

But these gains are now under threat, with conservative forces gaining more influence in Afghanistan and international aid money and interest in the country shrinking. Over the past few years, we have documented significant increase in threats, intimidation, and attacks against those at the forefront of promoting and protecting women’s rights. While the Taliban and other armed opposition groups are responsible for the majority of attacks, it is striking that women activists face threats and violence from all sides — warlords with links to the authorities, government officials, or even family members.

Over the past few years, we have documented significant increase in threats, intimidation, and attacks against those at the forefront of promoting and protecting women’s rights.

Responsibility

The Afghan government must start taking its responsibility to ensure protection of women human rights defenders seriously. There must be concrete steps to ensure that all allegations of threats or attacks against women human rights defenders reported are investigated, and that those responsible are brought to account. There is also a pressing need to build the capability of the Ministry of Women’s Affairs and its provincial counterparts.

The international community also has a crucial role to play, and must not abandon Afghanistan or those who put their lives on the line for human rights. There have been some noteworthy achievements supported by international donors since 2001, but up until now this has been on a limited, ad hoc basis. As aid money dwindles, international governments must prioritise support and resources to women human rights defenders in insecure and volatile areas of the country.

The international community also has a crucial role to play, and must not abandon Afghanistan or those who put their lives on the line for human rights.

The European Union Plus countries (the EU plus additional diplomatic missions) have recently launched a program that offers some promise. It will, once operational, offer emergency protection and ongoing monitoring for rights defenders. However, the strategy has yet to be tested, and it remains to be seen how successfully it will be implemented.

Today, April 7, I was fortunate enough to be in Kabul to launch our report together with some of the courageous activists who most need our continued engagement. Their commitment is inspiring, and provides hope for the future of Afghanistan. When I come back next time, I hope that the Afghan government and their international backers have turned their words and commitments into meaningful action.

This article was first published on foreignpolicy.com.