As the European Union hosts the ‘Forum for providing protection to Afghans at risk’ held on 7 October with the UK, USA and Canada also attending, Amnesty International Australia is calling on the Australian Government to provide an update on its efforts to help those still at risk from appalling human rights abuses at the hands of the Taliban.

To date Australia has publicly committed to helping just 3,000 people from Afghanistan fleeing the Taliban. While vague indications have been made that that will be the “floor”, there is still no confirmation of what the total commitment will be.

When the Syrian crisis escalated in 2015, Australia committed to a humanitarian intake of 12,000 refugees. Canada recently committed to taking 40,000 refugees from Afghanistan and the UK to 20,000. Now the EU and G7 member states are meeting to work out how else they can help, yet the Australian Government’s silence has been deafening since the first few weeks of the crisis unfolded.

Najeeba Wazefadost, a Hazara woman who fled the Taliban when she was 12, said: “While the initial response from the Australian Government was strong, very little appears to have been done in the past few weeks. And when you see how much Europe, the US and Canada are coming together to help even more, it makes you question how much Australia really cares about the plight of those still trying to flee the Taliban.”

Amnesty International Australia has been calling on the Government to:

- Increase its humanitarian intake to at least 20,000.

- Announce long anticipated improvements to the Community Support Programme that make it easier for people to sponsor refugees from countries such as Afghanistan.

- Provide certainty to those from Afghanistan already in Australia on temporary visas that they will be offered ongoing safety and protection in Australia.

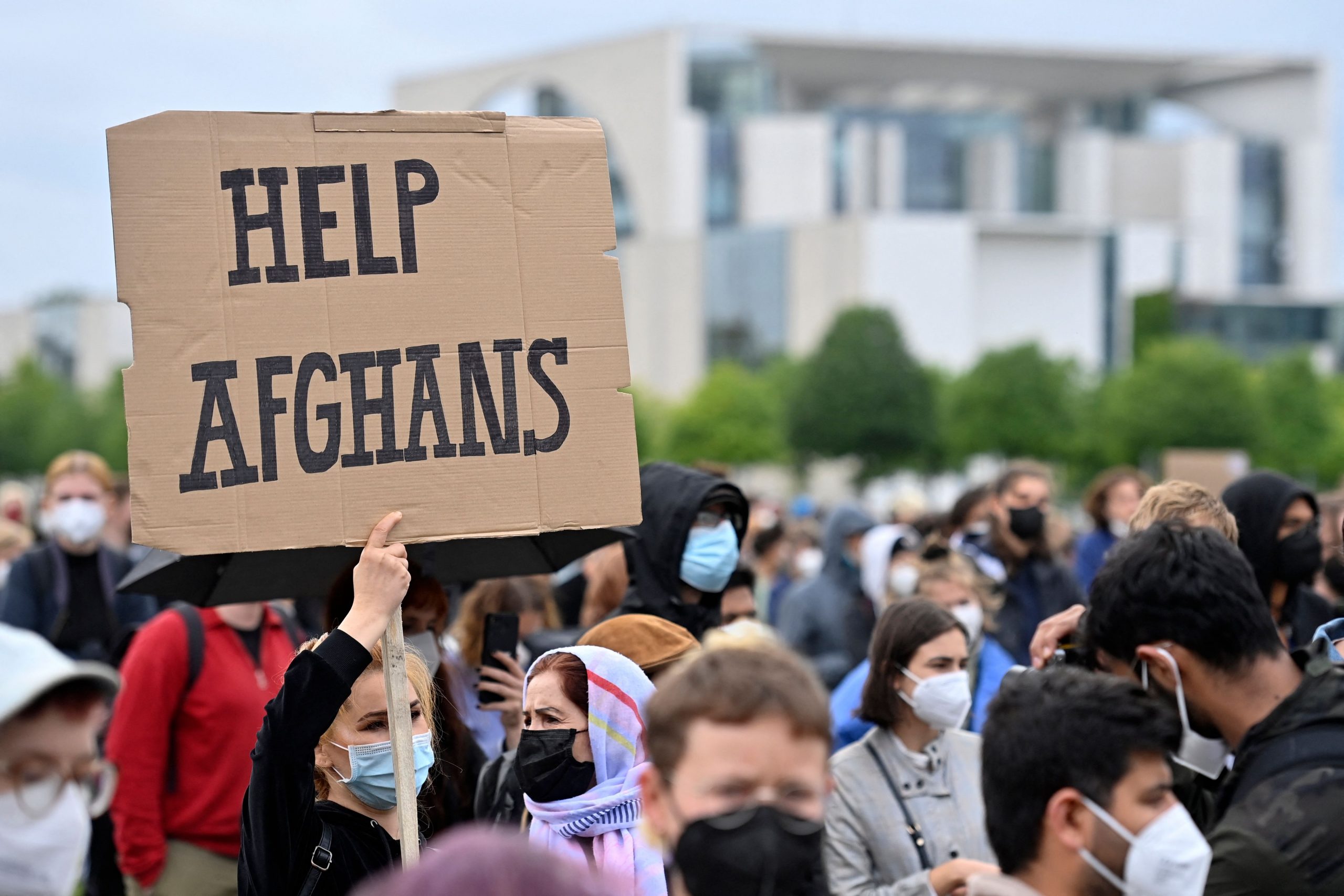

“We’ve seen an outpouring of concern for the people of Afghanistan, their fate and their futures. Public support for evacuation and resettlement must now be matched with political commitments. EU countries have an enormous responsibility to Afghans fleeing the Taliban. Evacuation is still possible, and EU countries must do everything they can to bring Afghans at risk to safety via land borders. The lives of the thousands of women and men who worked to promote and defend human rights, gender equality and rule of law, in their country depend on countries stepping up and evacuating people,” said Eve Geddie, Director of Amnesty International’s EU Institutions Office.

Amnesty International has written to countries attending the Forum asking them to step up efforts to secure evacuation of women activists, human rights defenders, civil society activists, academics, journalists, and marginalized groups, and others who are at heightened risk of retaliation from the Taliban.

Amnesty International Australia Refugee Advisor, Dr Graham Thom, said Australia’s silence on the issue of resettlement over the past several weeks is particularly embarrassing given our deep involvement in Afghanistan over the past 20 years.

“When those at risk after the Tiananmen Square demonstrations needed help, Australia stood up, when thousands fled Syria our government stood up – we cannot abrogate our responsibility to people in danger in Afghanistan in their hour of desperate need. New quarantine facilities are coming online, we have communities across Australia telling us they want to help, we have the capacity to take many more than 3000 people.”

Since the Taliban took power in Afghanistan on 15 August they have committed human rights violations with impunity. A recent research briefing by Amnesty International, the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and the World Organisation against Torture (OMCT) documented repression of the rights of women and girls, intimidation of human rights defenders, a crackdown on freedom of expression, reprisals against former government workers and possible violations of international humanitarian law. There have been targeted killings of people who formerly worked for the government, reports of death threats to family members of those who have fled, and – despite the Taliban’s public statements to the contrary – women and girls are being denied access to education and work, and barred from engaging in sport or politics.

Countries have already committed to annual resettlement quotas. Commitments to evacuate Afghans must be additional to this number. Any ‘creative accounting’ to fulfil resettlement numbers with people being evacuated would be unacceptable, as the number of places committed to are already limited.

ENDS

For more information or to arrange an interview, please contact media@amnesty.org.au +61 423 552 208

ABOUT AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL AUSTRALIA Amnesty International is a global movement of 10 million people standing up for justice, freedom and equality. We work to free people unjustly jailed, bring torturers to justice and change oppressive laws. We shine a light on great wrongs by exposing the facts others try to suppress. We lobby governments, and the powerful to make sure they keep their promises and respect international law. Together, our voices challenge injustice and are powerful enough to change the world. st1.amnesty.org.au