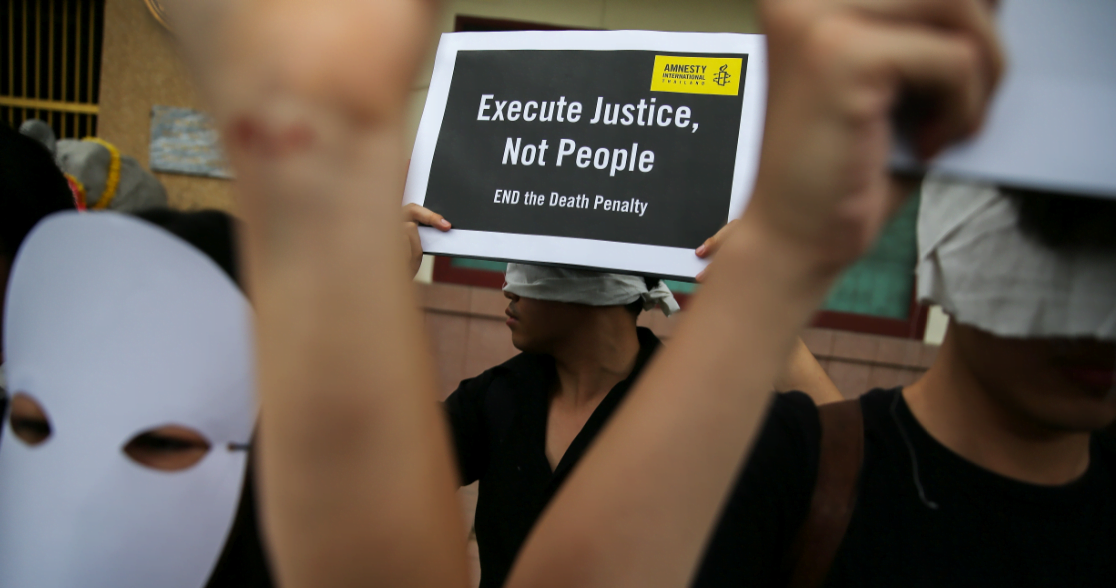

The unprecedented challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic were not enough to deter 18 countries from carrying out executions in 2020, Amnesty International said today in its annual global review of the death penalty. While there was an overall trend of decline, some countries pursued or even increased the number of executions carried out, indicating a chilling disregard for human life at a time when the world’s attention focused on protecting people from a deadly virus.

2020 executioners included Egypt, which tripled its yearly execution figure compared to the previous year; and China, which announced a crackdown on criminal acts affecting Covid-19 prevention efforts, resulting in at least one man being sentenced to death and executed. Meanwhile the Trump administration resumed federal executions after a 17-year hiatus and put a staggering 10 men to death in less than six months. India, Oman, Qatar and Taiwan also resumed executions.

“As the world focused on finding ways to protect lives from Covid-19, several governments showed a disturbing determination to resort to the death penalty and execute people no matter what,” said Agnès Callamard, Secretary General of Amnesty International.

“The death penalty is an abhorrent punishment and pursuing executions in the middle of a pandemic further highlights its inherent cruelty. Fighting against an execution is hard at the best of times, but the pandemic meant that many people on death row were unable to access in-person legal representation, and many of those wanting to provide support had to expose themselves to considerable – yet absolutely avoidable – health risks. The use of the death penalty under these conditions is a particularly egregious assault on human rights.”

Covid-19 restrictions had concerning implications for access to legal counsel and the right to a fair trial in several countries, including the USA, where defence lawyers said they were unable to carry out crucial investigative work or meet clients face-to-face.

Top five executing countries

China classifies the total number of its executions and death sentences as a state secret and prevents independent scrutiny. Therefore, Amnesty International’s figures for all known executions do not include executions in China. However, China is believed to execute thousands each year, making it once again the world’s most prolific executioner ahead of Iran (246+), Egypt (107+), Iraq (45+) and Saudi Arabia (27). Iran, Egypt, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia accounted for 88% of all known executions in 2020.

Egypt tripled the number of yearly executions and became the world’s third most frequent executioner in 2020. At least 23 of those executed were sentenced to death in cases relating to political violence, after grossly unfair trials marred by forced “confessions” and other serious human rights violations including torture and enforced disappearances. A spike in executions occurred in October and November, when Egyptian authorities executed at least 57 people – 53 men and four women.

Although recorded executions in Iran continued to be lower than previous years, the country increasingly used the death penalty as a weapon of political repression against dissidents, protesters and members of ethnic minority groups, in violation of international law.

Many countries in the Asia-Pacific region continued to violate international law and standards which prohibit the use of the death penalty for crimes that do not involve intentional killing. Yet, the death penalty was handed down for drug offences in China, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Viet Nam; for corruption in China and Viet Nam; and for blasphemy in Pakistan. In Bangladesh and Pakistan, death sentences were imposed by courts established through special legislation and which usually follow different procedures from ordinary courts. In the Maldives, five people who were below 18 years of age at the time of the crime remained under sentence of death.

The USA was the only country in the Americas to carry out executions in 2020. In July, the Trump administration carried out the first federal execution in 17 years, and five states put seven people to death between them.

Executions reach lowest number in a decade

Globally, at least 483 people were known to have been executed in 2020 (excluding countries which classify death penalty data as state secrets, or for which limited information is available – China, North Korea, Syria and Viet Nam). Shocking as this figure is, it is the lowest number of executions recorded by Amnesty International in at least a decade. It represents a decrease of 26% compared to 2019, and 70% from the high-peak of 1,634 executions in 2015.

According to the report, the fall in executions was down to a reduction in executions in some retentionist countries and, to a lesser extent, some hiatuses in executions that occurred in response to the pandemic.

Recorded executions in Saudi Arabia dropped by 85%, from 184 in 2019 to 27 in 2020, and more than halved in Iraq, from 100 in 2019 to 45 in 2020. No executions were recorded in Bahrain, Belarus, Japan, Pakistan, Singapore and Sudan – countries that carried out executions in 2019.

The number of death sentences known to have been imposed worldwide (at least 1,477) was also down by 36% compared to 2019. Amnesty International recorded decreases in 30 out of 54 countries where death sentences were known to have been imposed. These appeared to be linked in several cases to delays and deferrals in judicial proceedings, put in place in response to the pandemic.

Notable exceptions were Indonesia, whose 2020 recorded death sentences (117) increased by 46% compared to 2019 (80); and Zambia, which imposed 119 death sentences in 2020, 18 more than in 2019 and the highest recorded in sub-Saharan Africa.

Time to abolish the death penalty

In 2020, Chad and the US state of Colorado abolished the death penalty, Kazakhstan committed to abolition under international law and Barbados concluded reforms to repeal the mandatory death penalty.

As of April 2021, 108 countries have abolished the death penalty for all crimes and 144 countries have abolished it in law or practice – a trend that must continue.

“Despite the continued pursuit of the death penalty by some governments, the overall picture in 2020 was positive. Chad abolished the death penalty, along with the US state of Colorado, and the number of known executions continued to drop – bringing the world closer to consigning the ultimate cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment to the history books,” said Agnès Callamard.

“With 123 states – more than ever before – supporting the UN General Assembly call for a moratorium on executions, pressure is growing on outliers to follow suit. Virginia recently became the first US Southern state to repeal the death penalty, while several bills to abolish it at US federal level are pending before Congress. As the journey towards global abolition of the death penalty continues, we call on the US Congress to support legislative efforts to abolish the death penalty.

“We urge leaders in all countries that have not yet repealed this punishment to make 2021 the year that they end state-sanctioned killings for good. We will continue to campaign until the death penalty is abolished everywhere, once and for all.”