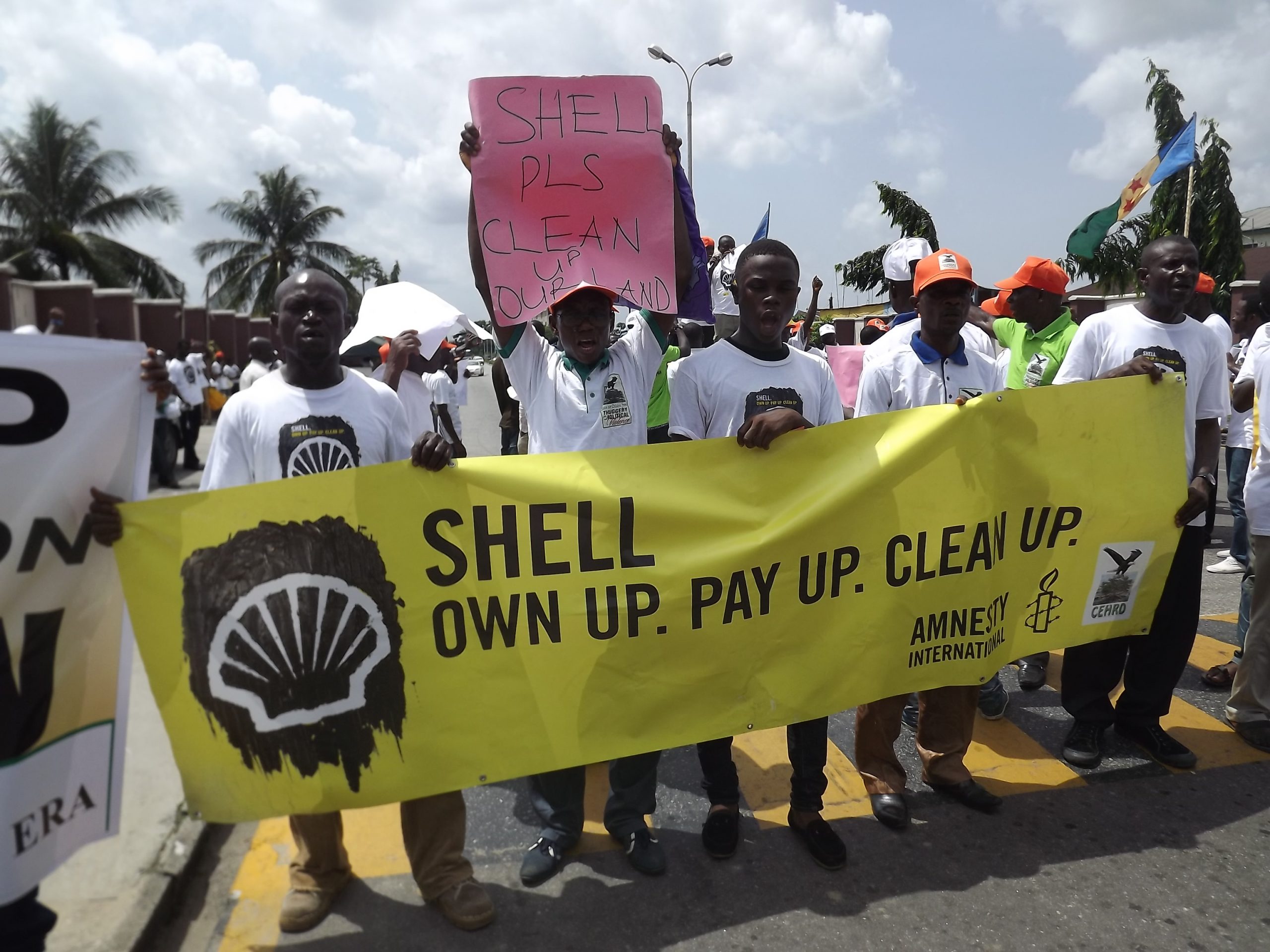

As millions took to the streets to protest rampant violence, inequality, corruption and impunity, or were forced to flee their countries in search of safety, states across the Americas clamped down on the rights to protest and seek asylum last year with flagrant disregard for their obligations under domestic and international law, Amnesty International said today upon launching its annual report for the region.

“2019 brought a renewed assault on human rights across much of the Americas, with intolerant and increasingly authoritarian leaders turning to ever-more violent tactics to stop people from protesting or seeking safety in another country. But we also saw young people stand up and demand change all over the region, triggering broader demonstrations on a massive scale. Their bravery in the face of vicious state repression gives us hope and shows that future generations will not be bullied,” said Erika Guevara-Rosas, Americas director at Amnesty International.

We also saw young people stand up and demand change all over the region, triggering broader demonstrations on a massive scale. Their bravery in the face of vicious state repression gives us hope and shows that future generations will not be bullied

Erika Guevara-Rosas, Americas director at Amnesty International

“With yet more social unrest, political instability and environmental destruction looming over the region in 2020, the fight for human rights is as urgent as ever. And make no mistake, the political leaders who preach hate and division in a bid to demonize and undermine the rights of others will find themselves on the wrong side of history.”

Protesters and human rights defenders faced rampant violence and state repression

Protest movements, often led by young people, rose up to demand accountability and respect for human rights in countries like Venezuela, Honduras, Puerto Rico, Ecuador, Bolivia, Haiti, Chile and Colombia last year, but authorities typically responded with repressive and often increasingly militarized tactics instead of establishing mechanisms to promote dialogue and address the protesters’ concerns.

The repression in Venezuela was particularly severe, with the Nicolás Maduro government’s security forces committing crimes under international law and grave human rights violations, including extrajudicial executions, arbitrary detentions and excessive use of force, that could amount to crimes against humanity. In Chile, the army and police also set out to deliberately injure protesters to discourage dissent, killing at least four people and seriously wounding thousands more.

In total, at least 210 people died violently in the context of protests across the Americas: 83 in Haiti, 47 in Venezuela, 35 in Bolivia, 31 in Chile, eight in Ecuador and six in Honduras.

Latin America is once again the world’s most dangerous region for human rights defenders, with those dedicated to protecting rights to land, territory and the environment particularly vulnerable to targeted killings, criminalization, forced displacement, and harassment. Colombia remained the most lethal country for human rights defenders, suffering at least 106 killings, mostly of Indigenous, Afro-descendant and campesino leaders, as its internal armed conflict continued to rage.

Mexico was one of the world’s deadliest countries for journalists, with at least 10 killings in 2019. It also suffered a record number of homicides but persisted with the failed security strategies of the past by creating a militarized National Guard and passing an alarming law on the use of force.

Gun violence remains one of the biggest human rights concerns in the United States, with too many guns and insufficient laws to keep track of them and keep them out of the hands of people who intend harm. A new rule announced by the Donald Trump administration in January 2020 has made it far easier to export assault rifles, 3-D printed guns, ammunition and other weapons abroad to spread rampant gun violence beyond US borders, particularly to other countries in the Americas. Similarly, in Brazil president Jair Bolsonaro signed a series of decrees and executive orders that, among other concerning outcomes, relax regulation on the possession and carrying of firearms.

Governments took aggressive stances against migrants, refugees and asylum seekers

The number of men, women and children to have fled Venezuela’s human rights crisis in recent years rose to almost 4.8 million – an unprecedented figure in the Americas – but Peru, Ecuador and Chile responded by imposing restrictive new entry requirements and unlawfully turning away Venezuelans in need of international protection.

Further north, the US government misused the justice system to harass migrants’ rights defenders, unlawfully detained children fleeing situations of violence and implemented new measures and policies to attack and massively restrict access to asylum, in violation of its obligations under international law.

As people continued to seek protection in the United States due to persistent, widespread violence, the Trump administration has pushed them into danger. It has forced tens of thousands to wait in dangerous conditions in Mexico under the disingenuously named “Migrant Protection Protocols” (MPP) policy, also known as “Remain in Mexico.”

The United States is forcing increasing numbers of asylum-seekers into secretive, rapid-deportation programs that eviscerate their right to counsel. It has also pressured neighboring countries into effectuating violations of the right to seek asylum, strong-arming Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras into signing a series of ill-conceived, counterfactual “Safe Third Country” agreements.

Following the Trump administration’s threats to impose new trade tariffs, the Mexican government not only agreed to receive and host forcibly returned asylum seekers under MPP, but also deployed troops to stop Central Americans from making their way to the US-Mexico border.

Impunity, the environment and gender-based violence remain major concerns

Impunity remains the norm across the region. The Guatemalan government undermined victims’ access to justice for grave human rights violations by shutting down the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) last year, before the government in neighboring Honduras announced the end of the Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH) in January 2020.

Environmental concerns continued to rise across the Americas, with the Trump administration formally announcing its intention to withdraw from the Paris agreement, while severe environmental crises in the Amazon affected Indigenous Peoples in Brazil, Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador. Brazil was hit particularly badly, with president Bolsonaro’s antienvironmental policies fueling devastating wildfires in the Amazon and failing to protect Indigenous Peoples from the illegal logging and cattle farming behind land seizures.

Having taken office at the start of 2019, president Bolsonaro swiftly put his wider anti-human rights rhetoric into practice through a number of administrative and legislative measures that threaten the rights of everyone in the country. Meanwhile, the emblematic 2018 killing of the human rights defender Marielle Franco remains unsolved.

Despite some progress and the growth of diverse women’s rights movements in the Americas, gender-based violence remained widespread. In the Dominican Republic police routinely raped, beat and humiliated women engaged in sex work in acts that may amount to torture. Little progress has been made in terms of women’s sexual and reproductive rights across the region. Authorities in El Salvador continued to criminalize women and girls – especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds – who suffer obstetric emergencies under the nation’s draconian total ban on abortion, while a girl under 15 gave birth every three hours in Argentina, the majority after undergoing forced pregnancies that resulted from sexual violence.

Human rights victories and reasons for optimism in 2020

The last year has also brought some positive news. By the end of 2019, 22 countries had signed the Escazú Agreement, a ground-breaking regional treaty on environmental rights. Ecuador became the eighth country to ratify the agreement in February, meaning just three more need to do so for it to enter into force.

In the United States, a court in Arizona acquitted the humanitarian volunteer Scott Warren of “harbouring” two migrants in November after he provided them with food, water and a place to sleep, and a federal judge reversed the conviction of four other humanitarian volunteers on similar charges in February.

The acquittal of Evelyn Hernández, who was charged with aggravated homicide after suffering an obstetric emergency in El Salvador, was another victory for human rights, although prosecutors have since appealed the verdict. Young women and girls also emerged at the forefront of the largely youth-led movements standing up for human rights that brought optimism for 2020, as evidenced by powerful feminist demonstrations in places like Argentina, Mexico and Chile.

“The ‘green wave’ of women and girls demanding sexual and reproductive rights and an end to gender-based violence showed unstoppable momentum across the Americas. From Santiago, Chile, to Washington, DC, their awe-inspiring performances of the feminist anthem ‘A Rapist in Your Path’ gave us the soundtrack to solidarity in 2019 and renewed optimism for what we can achieve this year,” said Erika Guevara-Rosas.

“As we enter a new decade, we cannot afford for the governments of the Americas to keep repeating the mistakes of the past. Instead of restricting people’s hard-fought rights, they must build upon them and work towards creating a region where everyone can live in freedom and safety.”