- Amnesty spokespeople at the court and available for interview

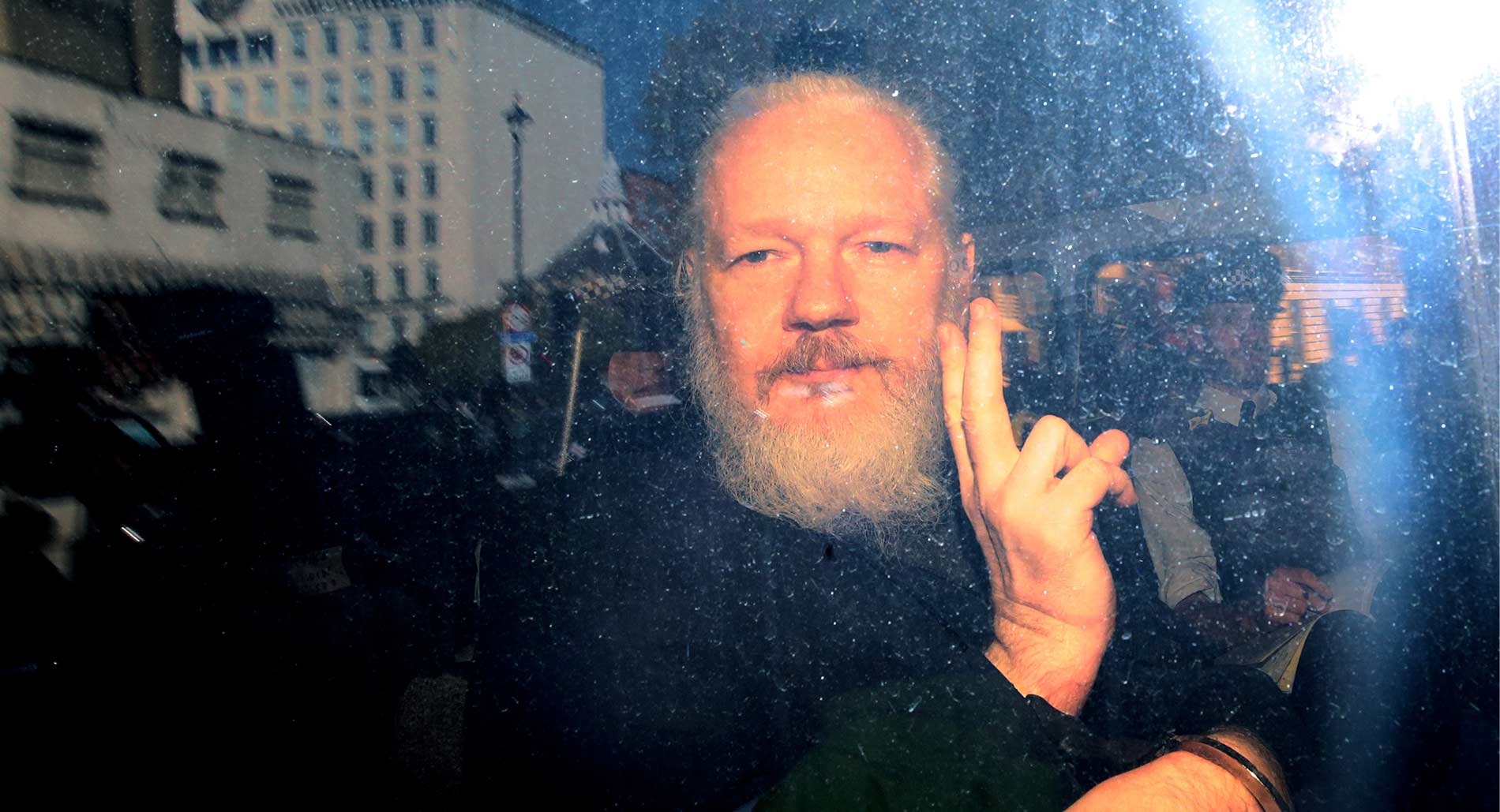

Ahead of an appeal hearing against the decision by a UK court not to extradite Julian Assange to the USA, Amnesty International’s Secretary General has called on US authorities to drop the charges against him and the UK authorities not to extradite him but release him immediately.

The call by Agnès Callamard follows an investigation by Yahoo News revealing that US security services considered kidnapping or killing Julian Assange when he was resident in the Ecuadorian embassy in London. These reports further weaken already unreliable US diplomatic assurances that Assange will not be placed in conditions that could amount to ill-treatment if extradited.

“Assurances by the US government that they would not put Julian Assange in a maximum security prison or subject him to abusive Special Administrative Measures were discredited by their admission that they reserved the right to reverse those guarantees. Now, reports that the CIA considered kidnapping or killing Assange have cast even more doubt on the reliability of US promises and further expose the political motivation behind this case,” said Amnesty Secretary General, Agnès Callamard.

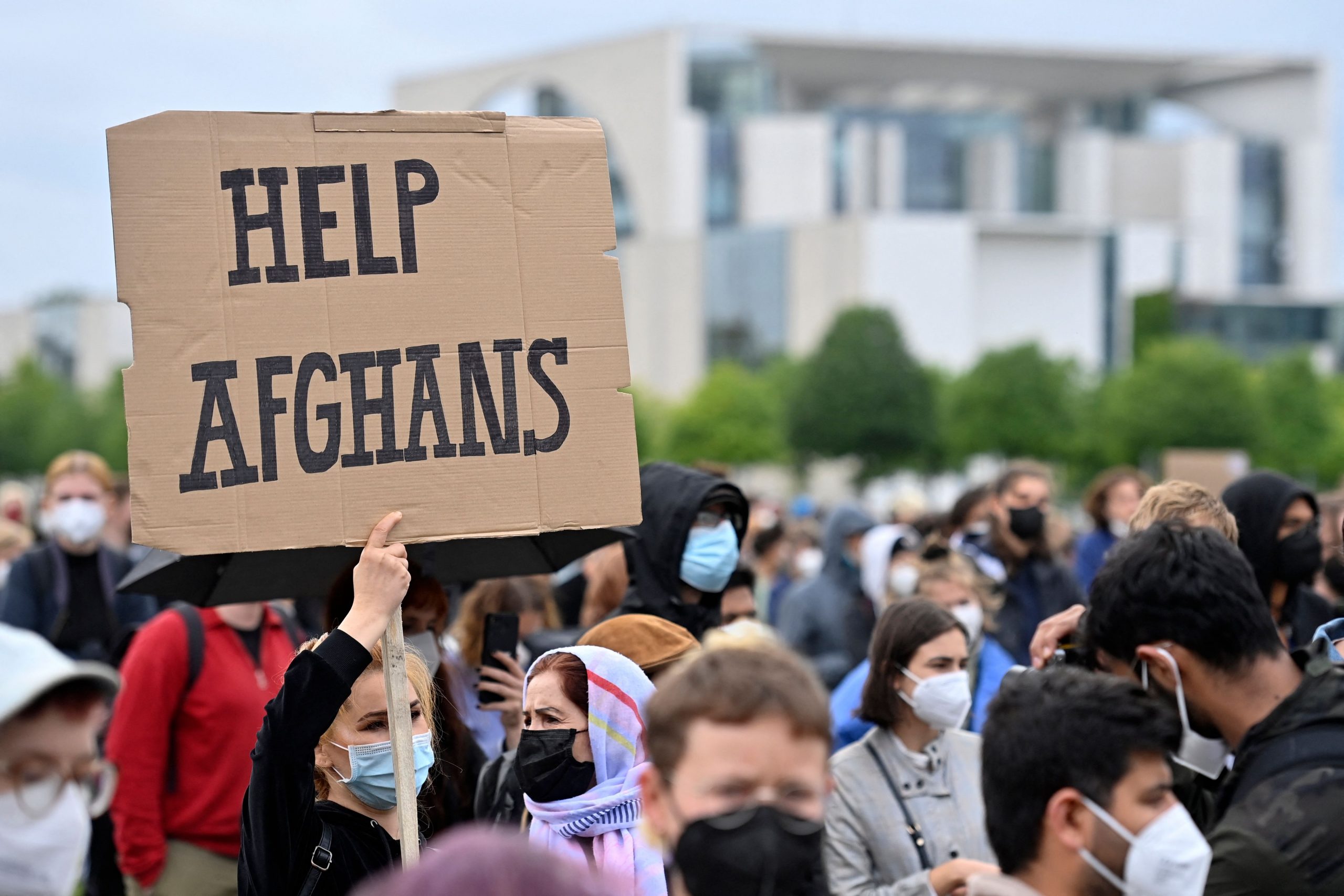

“It is a damning indictment that nearly 20 years on, virtually no one responsible for alleged US war crimes committed in the course of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars has been held accountable, let alone prosecuted, and yet a publisher who exposed such crimes is potentially facing a lifetime in jail.”

The appeal hearing, scheduled for 27-28 October, is expected to consider five grounds of appeal by the US, including the reliability of assurances offered by the US after a lower UK court ruled against Assange’s extradition in January 2021. Amnesty International has concluded that the assurances are unreliable.

The US charges allege that Assange conspired with a whistleblower — army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning — to illegally obtain classified information. They want him to stand trial on charges under the Espionage Act and the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act in the US where he could face a prison sentence of up to 175 years.

The US government’s indictment poses a grave threat to press freedom both in the United States and abroad. The conduct it describes includes professional activities undertaken by investigative journalists and publishers on a daily basis. Were Julian Assange’s extradition to be allowed it would criminalize common journalistic practices and permit the US and possibly other countries to target publishers and journalists outside their jurisdictions for exposing governmental wrongdoing.

“The US government’s unrelenting pursuit of Julian Assange makes it clear that this prosecution is a punitive measure, but the case involves concerns which go far beyond the fate of one man and put media freedom and freedom of expression in peril,” said Agnès Callamard.

“Journalists and publishers are of vital importance in scrutinizing governments, exposing their misdeeds and holding perpetrators of human rights violations to account. This disingenuous appeal should be denied, the charges should be dropped, and Julian Assange should be released.”

For more information or to arrange an interview contact at the court:press@amnesty.org stefan.simanowitz@amnesty.org +44 2030365599

BACKGROUND

The US extradition request is based on charges directly related to the publication of leaked classified documents as part of Julian Assange’s work with Wikileaks. Publishing information that is in the public interest is a cornerstone of media freedom and the public’s right to information about government wrongdoing. Publishing information in the public interest is protected under international human rights law and should not be criminalized.

If extradited to the US, Julian Assange could face trial on charges under the Espionage Act and under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. He would also face a real risk of serious human rights violations due to detention conditions that could amount to torture or other ill-treatment, including prolonged solitary confinement. Julian Assange is the first publisher to face charges under the Espionage Act.

For further information see